Towards science that is open and accessible to all: the puzzle of an expected but difficult to negotiate transition | larecherche.fr

How much would you be willing to pay to have access to a scientific study? The Dutch publisher Elsevier, which publishes more than one in five studies, charges an average of 25 euros per article. Now imagine that you were looking for the answer to a medical dilemma on which your life, or that of a loved one, depends, wouldn't you want to consult several articles at the risk of dangerously increasing the bill? A situation in which the American biologist Jonathan Eisen found himself and which gave rise to his commitment to science with free access for all. He is now Editor-in-Chief of PloS Biology, a successful example of an “Open Access” journal, whose publications are posted online for free, immediate access to everyone. Several tens of thousands of similar journals have emerged since the 2000s. Despite everything, around the world, around two-thirds of studies are still published in paid journals, inaccessible to the general public and to all research institutes that do not cannot afford expensive subscriptions with scientific publishers. There are many pirate platforms, such as SciHub, which offer the articles illegally, but an official institutional solution is pending.

Europe has tackled the problem head on with the creation of the S coalition, a group of 27 research funding institutions – national and international agencies, private foundations, etc. –, which has established 10 principles to initiate a change of course towards Open Access. The "plan S", which it put in place in January 2020, requires the results financed by its members to be published in open access for all, free of charge and immediately after publication. In France, for example, the National Research Agency, a member of the S coalition, will switch to Open Access for all the calls for projects it finances from its 2022 action plan. The Ministry of Education Superior, Research and Innovation also reaffirmed its support for the cause by extending the national plan for open science – initially from 2018 to 2021 – until 2024. Unveiled on July 6, 2021, this second three-year plan displays a target of 100% open access publications by 2030 and a budget multiplied by 3 (from 5 to 15 million euros per year).

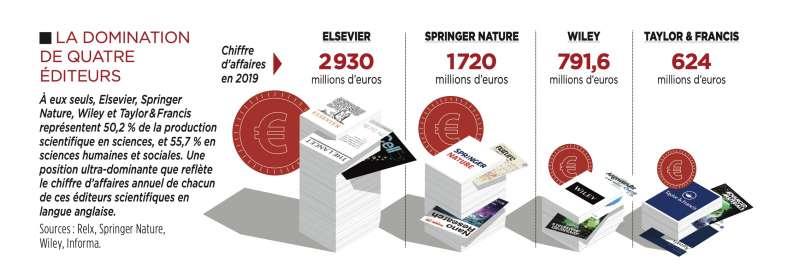

Outside Europe, the idea of Open Access is also booming in the United States, China, Australia and Canada. For Matthew Day, director of open access policies at the British publisher Cambridge University Press (CUP), "the debate is no longer whether academic journals will take the step towards Open Access, but rather how to achieve to this transition in a fair and sustainable manner." Indeed, it is a whole economic model that needs to be reviewed – that of scientific publishing – and the paths towards open access research are multiple. Thus, if plan S advocates Open Access, it does not decide on the way forward. Opposite, the scientific publishing industry is also very diverse. Four commercial publishers, including Elsevier and Springer Nature, hold more than 50% of the market and regularly amass record profits of more than 30% while learned societies and nonprofit publishers seem worried about their survival in a world where their journals would become free.

Sometimes difficult negotiations

The University of California (UC), a flagship of public research in the United States, has undertaken to renegotiate its contracts one by one to include Open Access. An approach initiated by its researchers. Nine new agreements have been put in place following negotiations with publishers, but reaching a compromise with the giant Elsevier has not been easy. Differences between the publisher and the university over the total cost of the contract and the possibility of publishing in open access in all the journals of the publisher, without exception, forced UC to leave the negotiating table loudly in 2019, thus depriving themselves of access to major scientific journals such as Cell and The Lancet. It will finally take two years for the publisher to return to the university with a satisfactory proposal: an “all-in-one” agreement, signed last March, which includes reading and publication costs.

"Transforming" chords

Such so-called transformative agreements put an end to a practice that has been widespread – and criticized – until now: “double dipping”. The principle of double dipping is simple: to cover the publication of an article in open access, journals charge authors fees of up to several thousand euros so that they can publish at home; the same article is also invoiced in the many reading subscriptions that the publisher sells to research institutes. Although it is not the same people who pay, the journal therefore pockets several payments for the same article. As part of transformative agreements, such as the one between UC and Elsevier, the publisher has committed to publishing all the work of the American university in Open Access, in return for the payment of publication fees. The right to read – the main service sold to universities until then – is now included free of charge in the contract because, if such agreements were to become widespread, all articles would be published in open access.

The transfer of publication costs from the reader to the authors is already worrying research institutes which publish a lot and are afraid of seeing their costs explode. To remedy this, the agreement between UC and Elsevier includes discounts on publishing fees and caps the university's bill at $13 million per year, a price comparable to the old reading subscription between UC and Elsevier. While it remains expensive, Ivy Anderson, co-chair of the negotiating committee for UC, believes that the important thing was to lead by example: “it is often thought that institutions that are very research-oriented and publish a lot do not have the means to switch to Open Access. I think this deal demonstrates that it is possible to find common ground with publishers to negotiate an affordable deal that keeps costs down.”

Challenges of the "golden path"

But this type of approach, known as the “golden path” to Open Access, could be difficult to generalize and still does not convince all players in the sector. First among scientists: not all of them necessarily have behind them an institution with enough means to cover the costs of publication in open access.

Editors are also shared. It is not surprising to see multinationals like Elsevier dragging their feet to abandon a model that has been very profitable for them and move to open access. But “non-commercial publishers”, learned societies and university presses, have a more ethical vision, although constrained by a sometimes difficult economic reality. Matthew Day and his publisher, Cambridge University Press (CUP), share the ideal of UC negotiators and Open Access advocates: that of a better world, where those who cannot afford to pay to read science (scientists in developing countries, doctors who are not attached to large hospital structures, public health officials, the voluntary sector, engineers, etc.) would finally have access to it. In practice, this is a risky bet because the transition to transforming agreements translates into a projected 15% shortfall for CUP. A non-negligible percentage, especially for a non-commercial publisher like CUP. What to call into question the openly pro-Open Access orientation of the publishing house? Not really, although Matthew Day concedes that “economic analysis from the point of view of a scientific publisher is really difficult. Those who read our journals will no longer pay because it will no longer be necessary […] and those who publish will have to cover the costs, but they do not necessarily have more money!” Indeed, research budgets are often tight and Matthew Day estimates that “three-quarters of authors published at CUP cannot afford to pay publication fees to date”.

To address this problem, the publisher hopes to engage more than 75% of its authors in transformative agreements by 2025, reallocating funds formerly allocated to reading subscriptions towards the financing of publications. But that's not all: in order not to fall into the red, CUP cannot afford to lose authors who would go to other journals because its own have become paying. A very real fear for publishers if only a minority of them play the game of the golden way, while the others continue to publish, at no cost to the authors, in pay-per-read journals. Faced with this dilemma, however, not all publishers are equal. At issue is the current functioning of the research evaluation system. Indeed, nowadays, the quality of a scientist's research is too often reduced to the reputation of the journals in which he publishes. In such a context, researchers have every interest, in order to advance their careers, in publishing their work in the most reputable journals… which are, for the most part, the property of large commercial publishers. However, there is no reason for this to change with the transition to Open Access, especially if the “golden path” model economically weakens non-commercial publishers. Unesco even anticipates an aggravation of the problem; the UN agency has already warned, in a recent statement, against a full transition to the golden path, which could further strengthen the dominant position of commercial publishers.

Plan S solutions

How to prevent this scenario from happening? Plan S may well be part of the solution, as it tackles, one by one, the challenges posed by the Golden Path: Coalition S funding agencies will bear the cost of open access publishing, at least beginning ; these same agencies, such as the National Research Agency in France, are trying to change the criteria for allocating their funding by favoring the quality of the work of researchers rather than the reputation of the journals in which they publish; finally, launched simultaneously in 17 countries, plan S (for "shock") encourages a majority of publishers to offer solutions for publishing in Open Access at the same time, thus reducing competition for authors from the point of editors view. Nevertheless, if the journal chosen by scientists covered by Plan S does not distribute the study freely as soon as it is published, it is up to the researchers to do so by putting their work online on the site of their choice, an open archive. For example. It is the “green path” towards Open Access and, at present, it is the most developed approach in France.

France and the "green route"

Indeed, at the national level, France has only one transformative agreement in place to date, with Cambridge University Press. Couperin – a consortium of more than 250 higher education and research establishments – is tasked with negotiating national pro-Open Access contracts with publishers, but the results are mixed. The agreement concluded in 2019 with Elsevier, for example, has been singled out. Although it concedes reductions on open access publication costs, it does not tackle double dipping: Open Access or not, reading the publisher's journals is always chargeable and, as summed up by the Société Française of Physics, "in its negotiated version, free access will be neither complete nor immediate".

For sociologists Quentin Dufour, David Pontille and Didier Torny, who study the economics of scientific publications at the Center de sociologie de l'innovation des Mines de Paris, southern European countries are less interested in transformative agreements , as they have few commercial publishers in their territory. Furthermore, “the creation of a national archive, without equivalent in other European countries, just like article 30 of the Law for a Digital Republic [which authorizes authors to make their studies freely accessible after a period of embargo, Editor's note], draw a national landscape very favorable to the deposit of studies and their dissemination through open archives”. Created by the CNRS in 2001, HAL is an online multidisciplinary platform on which researchers can submit their work, whether published or not. Since 2016, the Law for a Digital Republic has authorized researchers financed by public funds to put their work online after an embargo period of a maximum of one year, regardless of the clauses laid down by the publisher or the review. A first step that Plan S pushes even further by imposing the immediate distribution of free access content: thus, in France, all publications resulting from projects funded by the National Research Agency must be deposited on HAL under a license free, from 2022.

The Value of Scientific Publishing

Even more than the golden route, the green route is feared by scientific publishers, commercial or otherwise. The reason ? It authorizes the distribution, free of charge and outside their platforms, of scientific articles, the "product", which the journals have until then marketed in the form of reading subscriptions. For Matthew Day, the principle of the green lane without an embargo period – which Plan S provides – calls into question the value placed on the work provided by publishers. He explains: “When we talk about this option, what is implied is that we want it to be the final, peer-reviewed version that is made available for free, not just the version preceding submission to the journal.” However, this makes a significant difference, insists the CUP representative. Because, to assess the validity of the results of a study and decide whether or not it deserves publication, the journals bring together a committee of experts. A costly and laborious task of coordination, especially when you know that several million articles are submitted for publication each year. In addition, if selected, the study is generally reworked by the researchers to perfect its content, but also by the journal, which edits, lays out, and sometimes illustrates, the final version. There is therefore a lot of work provided by the scientific editors to achieve the published version. But Matthew Day does not see how to finance it with a green path which, unlike the golden path, does not provide for any way of remunerating the reviews. However, as Dufour, Pontille and Torny point out, "most of the work that allows a scientific article to see the light of day is provided free of charge by researchers, starting with the various writing and evaluation phases" . It is difficult, in such a context, to justify the disproportionate profits of commercial publishers, which suggest publication costs that are still too high for the services provided by the journal, however laborious.

Furthermore, certain abusive practices – double dipping, the price of reading subscriptions, the record profits of commercial publishers – have eroded trust between the scientific community and publishers. Another example: according to a report by SPARCEurope, journals continue to take over the copyright of the work they publish, limiting the reuse of scientific data for future research. A practice still denounced in an appeal co-signed by 800 European universities in May and in the sights of the new national plan for open science which provides for the creation of a national platform for hosting scientific data, "Recherche Data Gouv".

While obstacles remain, the ideal of open access science is advancing. Green, golden or another option? Different countries, institutions, publishers and funding agencies are experimenting to shape the scientific publishing of tomorrow. Although their visions and interests are multiple, all these players agree that the industry will come out of it profoundly transformed.

by Marie-Cécilia Duvernoy

Image credit: © Riccardo Milani / Hans Lucas / Hans Lucas via AFP

Infographics: Medhi Ben Yezzar

![PAU - [ Altern@tives-P@loises ] PAU - [ Altern@tives-P@loises ]](http://website-google-hk.oss-cn-hongkong.aliyuncs.com/drawing/179/2022-3-2/21584.jpeg)

![Good deal: 15% bonus credit on App Store cards of €25 and more [completed] 🆕 | iGeneration Good deal: 15% bonus credit on App Store cards of €25 and more [completed] 🆕 | iGeneration](http://website-google-hk.oss-cn-hongkong.aliyuncs.com/drawing/179/2022-3-2/21870.jpeg)

Related Articles